This article has been written for us by Helen Gillingham. Helen is chairperson of the Sustainable Food Group of Transition Town Wellington. She is a full-time self employed beauty therapist who has a passion for the natural world and a real concern for the future of our planet and human civilisation and writes “I have been doing all I can to help spread the message about climate change and how we can help as individuals. I have been growing my own food at my allotment for 16 years and have been an active member of TTW for 13 years teaching the public how to grow veg, and planting fruit, nuts and herbs in our communal green spaces.”

Towards a Sustainable Food System

Two necessities unify all humans on the planet – the need for food on the table and a roof over our heads; and our worldwide land use shows this.

Although we may feel urban sprawl is taking up a lot of land, it actually only occupies 1% of Earth’s habitable land; meanwhile agriculture has grown from 5% around 300 years ago to a massive 50% today (source https://ourworldindata.org/land-use). How we use the planet’s surface makes a huge impact on the environment – around half of the global greenhouse gas emissions (GGE) – 44–57% – are produced by industrial food production alone (source https://www.grain.org/e/5310). This is from 6 main processes: deforestation; production; waste; transportation; processing; and packing and refrigeration.

I will discuss these 6 factors in this article and show how we have not only the potential to reduce carbon emissions and heal natural ecosystems, but also effectively lock up carbon in the soil by using innovative regenerative farming techniques. This will mean radically changing our current food systems; but if it holds the answer to reversing climate change and ecological collapse, then change on a worldwide scale is necessary. Our actions as individuals and communities all across the world are key.

Deforestation

The process of turning wild land over to agriculture has been happening throughout human history. Natural land, be it forest, peatland, wetlands, prairie or scrub, stores many nutrients and carbon in the soil and plants, increasing fertility year on year; and this fertility will last for some time after we start to grow crops on it.

It doesn’t last long as annual crops are greedy, ploughing releases carbon stored in the soil and destroys the beneficial mycorrhizal networks of fungi and other micro-organisms within it. Further damage occurs through the use of slash-and-burn agriculture to the extent that we are now burning the lungs of our planet, the precious rainforests – the last wildernesses to sacrifice. As the soil has degraded over the years, access to natural, fertile land has caused increasing conflict.

Agriculture is responsible for 70–90% of world deforestation, and this accounts for 15–18% of Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GGE). Much of this deforestation is to make more space to grow soya and other crops to feed our intensive livestock farms; or palm oil to produce our biscuits, chocolates and face creams. In the last 50 years, 140 million hectares of fertile land has been taken over to produce soybeans, palm oil, canola and sugarcane.

We need to protect remaining wild land and try to return as much as we can to nature. Charities and carbon & ecological offsetting schemes may hold some hope for areas of wilderness to return, but many people have claims on the land, either small farmers or big multi-national corporations.

We either need new international laws to stop these large entities from industrialising the land; or change needs to be financially viable for farmers and help feed and pay local people who rely on the current system. Livestock farming as pioneered by the Savory Institute and latterly the Knepp estate (as depicted in the book “Wilding” by Isabella Tree) could give an alternative hope for the return of wild land, in temperate climates at least.

In Europe and North America for example, much of the natural landscape would have been wood pasture; a mixture of trees, grassland and scrub. (Evidence that wood pasture formed much of the landscape in Europe can be seen from our native oaks – a tree which does not grow in closed canopy but needs space to spread its branches and the closed canopy theory of plant succession doesn’t include the influence of native herbivores. You can read much more about this in “Wilding”, chapter 5).

Huge herds of wild herbivores were vital to maintain the balance of this ecosystem, eating some saplings, creating open spaces and maximising “woodland edge” – the place which we understand holds the greatest biodiversity. Their hooves would churn up the soil, allowing wildflowers to grow, and their poo would fertilise the grass. The land was never overgrazed as the herds were moved on frequently and numbers kept in check by predators, wolves, lynx, lions, etc.

In our brief human existence we have, unfortunately, reduced the number of wild herbivores to a fraction of the huge herds they once were, (the extinct aurochs, native of Europe and the bison of the North American prairies for example). It may be impossible to replace these species but if we replaced the herds with hardy breeds of cattle, wild deer and ponies, we could recreate the landscape as it once was with space for insects, birds and other beneficial creatures to return, and ultimately restore the carbon and nutrients to the soil.

There is evidence that both too many or too few grazing animals can lead to habitat degradation. In the highlands of Scotland too many deer have stripped the hills of its trees, whereas fewer reindeer in Finland have led to more closed canopy forest. In both cases the ecosystem has become unbalanced.

In some countries, overgrazing can turn scrubland to desert, because the herbivores are never removed from the land to allow the grass to recover. However, it’s been found that removing them completely takes away the nutrients found in their urine and manure as well as reducing seed dispersion, and the grass and trees grow less well. A balance needs to be found between the numbers of herbivores and the duration of grazing, and where there are no longer lynx and wolves as apex predators, farmers can keep numbers in check by culling animals and selling the high-quality meat.

There are more controlled / fewer wild methods of farming that also mimic natural ecosystems and can suit smaller farms. “Holistic mob grazing” is a type of rotational grazing where cows are moved on daily to new pasture, but intensively graze a smaller space, mimicking larger herds. In agroforestry systems, permanent pasture is inter-dispersed with rows of nut and fruit bearing trees to provide a second yield from perennial crops as well as meat – echoing the mix of grassland, scrub and woodland in a natural landscape.

Deforestation in tropical regions cannot be successfully replaced by grazing because it’s simply too hot to grow grass, so removing the trees has led to desertification. However, the charity “Trees for the Future” has been helping farmers create forest gardens containing a polyculture of edible and useful plants, which not only rebuilds the soil and reclaims the desert with trees that feed local people but means trees need not be felled in the future; the profit being in the harvest, not the wood.

This is not such a new idea – we used to use many more perennial crops such as nuts, and we can look towards more perennial crops to sustain us in the future, rather than relying on the fairly limited range of foods we now eat. In Europe, the Mesolithic people were part of the “nut age” where hazels were used as a staple food and building material. These hunter–gatherers planted food bearing trees close to their homes, and this ease of sourcing food meant they had the most leisure time in human history.

Growing your own vegetables is a luxury for people that have free time, something of which our modern lives show a distinct lack. But if you could just harvest, for free, from public space locally to you, wouldn’t that be wonderful? This is one reason why many community environmental groups across the country are so keen on planting fruit and nut trees from which everyone can forage from for free. It provides free food both to those with enough money but little time, and those who struggle financially. It also reduces the carbon footprint for all, as well as providing a fantastic habitat for wildlife.

Production

Monoculture crops, Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), fertilisers and agri-toxins account for 11–15% of GGE.

Industrial arable agriculture uses tractors and other machinery that burn fossil fuel, agrochemicals require lots of fossil fuel to produce, and nitrous oxide (another potent greenhouse gas) is released from artificial fertilisers into the atmosphere. Even the very act of ploughing itself, exposes carbon which is held in the soil to oxygen in the air, forming carbon dioxide. We have been ploughing for centuries, but now we have bigger and bigger tractors that do this much more effectively than by horse drawn plough.

Just because a tradition of breaking up the soil surface to plant seed is passed down generation after generation, does not mean to say it’s the best way of raising crops. Studies have shown that using new machinery to sow fresh seed into last year’s stubble (direct drilling) and using intercropping to control weeds and surface run off, gives higher yields once the soil rebuilds itself and the worms and mycorrhizal fungi return. This will mean that fields of corn or wheat are still perfectly possible without ploughing.

We are becoming totally reliant on agrochemicals to grow arable crops on degraded soil. These chemicals are a huge cost to the farmer as well as destroying the soil’s micro-organisms that make it fertile in the first place. The importance of switching to organic farming practise cannot be understated, as the impact on both soil fertility and insect life is causing the crash in our ecosystems.

There are many studies now (see the links below) showing that once the soil starts to improve by regenerative farming techniques, you can get higher yields in relation to ongoing cost. A report published by the Economics of Land Degradation Initiative in September 2015, said if sustainable land management was rolled out around the world, as much as $75.6 trillion could be added to the economy through jobs and increased agricultural output.

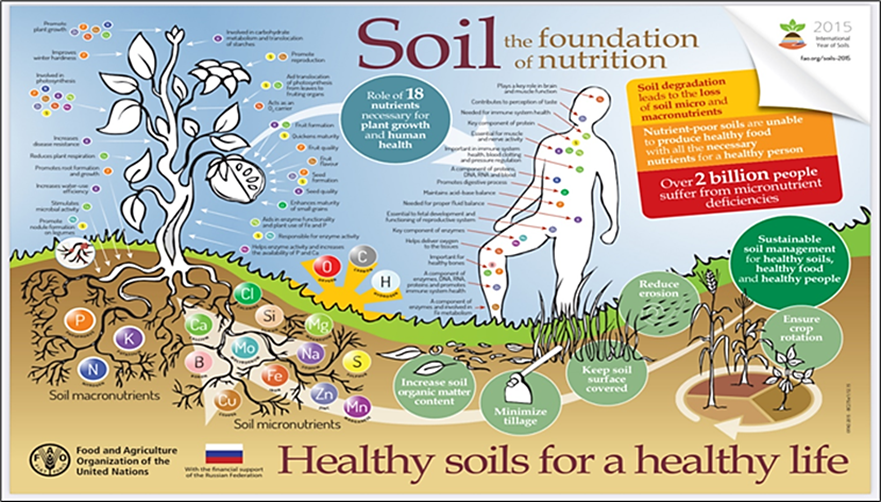

The degradation of soils is also impacting our health, as the soils contain less of the micronutrients that we need, and the plants can have residues of chemicals that could cause cancer or intestinal diseases. Studies have shown how much more nutritional value organically grown food has, which is highlighted in the infographic below.

The act of not ploughing and not adding chemicals allows mycorrhizal fungi to grow, and a sticky glycoprotein called glomalin to form. This revolutionary soil secret was discovered in 1996 by Sara Wright and explained in Graham Harvey’s book “Carbon Fields” (2008). Glomalin attaches to particles of sand, silt, clay and organic matter, forming lumps of soil “aggregates” giving soil its structure. Glomalin is made from protein and carbohydrate sub-units both containing carbon – comprising 20–40% of the molecule. It protects the carbon from being decayed by soil microbes, so the more mycorrhizae in the soil, the more carbon is stored.

Amazingly, the world’s soils hold more carbon as organic matter than all the vegetation on the planet, including all the forests: 82% of carbon in the terrestrial biosphere. It’s likely that different situations will capture different levels of carbon; however, there is a new invention, the “yard stick”, that is making it easier to measure levels before and after regenerative management.

A University of Georgia study demonstrated 3 tons of carbon per acre per year (3 tC/ac/yr) drawdown via a conversion from row cropping to regenerative grazing, and many other studies are finding the same thing. After the Paris Climate Change talks in 2015, it was calculated that if we could increase the carbon stored in soils by just 0.4% per year, it would equal that released in the atmosphere yearly, halting climate change. So, there is real hope that this will be one solution to this problem, as well as improving our soil fertility and food security.

Changing methods of farming will be a huge requirement for farmers, not just a big task to learn new methods, but also financially to change machinery. As individuals we can support this all we can, lobbying and petitioning our government to make sure they give farmers the subsidies they need to make the change, and passing on education from trusted resources such as the Soil Association and Pesticide Action Network. (Also see below for articles you can share.)

Wheat, corn, barley etc. will be able to benefit from new methods of intercropping and over sowing, but it isn’t currently possible to grow some of annual vegetables such as potatoes in a no dig way, apart from on small scale with market gardens, mixed smallholdings and growing our own. So whereas the average person could still buy bread and other grains off the shelf, we could go back to buying our vegetables from smaller local farmers, like we used to in this country 100 years ago, and as is still practiced in many parts of the world today.

I want to make the point that the facts and figures I’m quoting from grain.org are for industrial farming. Three quarters of worldwide agricultural land is for industrial use, which feeds only half of the world’s population, mainly in cities and the more economically developed countries. One quarter of agricultural land is not industrially farmed, and actually feeds the other half of the world’s population; and up to 80% of those who live in less economically developed countries. These are small farmers who graze small amounts of livestock on permanent pasture and use animals to help fertilise vegetable crops.

The key is improving the soil. New techniques can apply principles learnt from smaller farms on a large scale, choosing what technique suits each situation best. For instance, in a mixed regenerative farm, a mixture of green manures can be sown which all have different root depths and fix different nutrients in the soil, to improve the ground ready to give a good yield in the next crop. The best way of incorporating these without digging is by allowing animals to eat them, processing the vegetable matter in their gut and giving their manure as a reward. This has been scaled up to successfully restore degraded soil in huge farms in America, (check out Kiss the Ground docufilm on Netflix).

The distinction needs to be made that industrial farming is the problem, not whether you are eating meat or choosing not to. If half of the world can be fed on one quarter of the world’s agricultural land in a non-industrial way, it shows how inefficient industrial agriculture actually is. The question isn’t if we can feed the world’s population without industrial agriculture; we most certainly can, and more. But if we don’t stop ploughing and spraying agrochemicals then we won’t have an ecosystem or climate to support food growing at all.

A huge amount of our arable crops is being farmed as feed for livestock. In the UK, Simon Fairlie estimates it is around 50%; worldwide is about 40% (source: http://www.fao.org/3/ar591e/ar591e.pdf). Animals raised in huge concentrations in the abhorrent CAFOs have the highest carbon footprint, not only from the water and infrastructure they need but mainly because they eat feed from arable crops.

For each serving of meat, a cow fed on grain is eating food that could be eaten by humans, multiplying the problem of intensive arable farming 10 to 20-fold, depending on whether you are looking at protein conversion (10:1) or total calories (20:1) and which data source you use. But what is not debated, is how feeding cows an unnatural diet does the cows no good at all. Cows that eat grass produce less methane than grain fed cows, and studies have shown that if their diet also contains wildflowers such as birdsfoot trefoil, that would have been found on organic permanent pasture, this also reduces their methane emissions.

It’s not just the environment that suffers from industrially raised meat; our health does too. Not only do hormones and antibiotic use in industrial meat production affect our health – cattle fed on grain also store a different kind of fat, which then passes on to us. All the studies on how detrimental red meat is for us, causing heart disease and high cholesterol, have been done since the industrialisation of meat, since they were fed on grain.

Meat from animals reared in functional ecosystems on a diverse pasture is higher in omega 3. It means a healthy ratio between omega 3 and 6, which allows us to benefit from omega 3 essential fatty acid’s potent anti-inflammatory properties. (Inflammation has been scientifically proven to be associated with nearly all modern chronic disease). Grass-fed meat is rich in conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). CLA is associated with a lowered risk of heart disease and may help prevent and manage type 2 diabetes and has also been shown to reduce cancer risk by blocking the growth and metastatic spread of tumours.

Grass-fed meat, compared to grain-fed meat, contains a powerhouse of minerals and vitamins, including bioavailable protein, zinc, iron, selenium, calcium/or B12. Phytonutrients’ or ‘phytochemicals’ are primary or secondary metabolites found in plants and recognised to have nutritional quality attributes and powerful potential health benefits.

Researchers have found that healing phytochemicals such as terpenoids, phenols, carotenoids and antioxidants with anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective and anti-cancer effects, are found in the meat and milk of livestock who have access to healthy, diverse pastures, but less so in those grazed on monoculture pasture; further reduced or absent in the meat and milk of grain-fed animals. All of these nutrients are critical for fighting disease and maintaining health – especially when plant-based foods can contain fewer nutrients due to the degradation of soil with inorganic farming, or for people in parts of the world that rely on a meat-based diet.

The mainstream environmental message is to eat less meat, but we can see it’s not that simple. The distinction between industrialised farming where animals are fed on arable crops, needs to be separated from livestock fed on their natural diet; on permanent organic pasture, or used in a rotation to improve the soil on regenerative farms.

We often categorise agriculture into two groups; either arable/pastoral, or meat/plant based, but these definitions are only half of the picture; we really need 3 categories. Arable for human consumption, arable for industrialised meat, and pastoral. Even the source I have quoted for land use (https://ourworldindata.org/land-use) fails to distinguish these categories, see this table below:

It’s a fantastic infographic, but like so many others, it doesn’t separate pasture fed livestock from grain fed, showing the combined figure of 77% of agricultural land. We know industrial meat has a huge environmentally damaging effect, whereas pasture fed, regenerative and rewilded animals can actually help our soils lock in carbon and increase diversity in our ecosystems. What’s more, herbivores in particular, feeding on grass, can be farmed on marginal land that is unsuitable for arable crops, where grass grows well but many agrochemicals are needed to grow grain.

The two systems are poles apart and should not be classed as the same thing, because the problem with only looking at part of the picture is you can end up coming to an environmentally unfriendly conclusion.

This paper concludes that eating chicken and pork is less harmful than eating red meat because they are smaller creatures needing less infrastructure and eating less imported feed therefore have a lower carbon footprint, but we know much of the Amazon rainforest is being burnt to produce soya and 90% of all soya grown is to feed livestock!

It is very hard to farm chickens and pigs in large quantities as sustainable meat, and not supplement them with industrially farmed feed; only small numbers are starting to become part of regenerative mixed farms, but pasture fed chickens and forest raised pigs are a niche luxury at the moment. We are now in a critical time to save ourselves from climatic disaster, so we need to see the full picture so we can do what is right to have the most benefit.

Waste

The industrial food system wastes half of the food it produces at a farm level. We then waste more food once it reaches the supermarkets and our homes, accounting for 3–4% of GGE.

This highlights another way that our industrial food system is not as high yielding or as efficient as we think. We can help reduce food waste as a community if we tried; setting up gleaning projects to take waste food from the farm directly to people who need it, such as with the Gleaning Network in the UK and the Suncoast Gleaning Project in the US.

We could set up a food waste cafe like ReRooted in Tiverton, or a community pantry. There are also many ways you can help with food waste as an individual; the “love food, hate waste” website has lots of tips for cooking with leftovers and storing food correctly, and how to plan your meals and not waste any food in the first place.

Transportation

We may feel that food grown on the other side of the world has nothing to do with us, but that’s not true. Food can be produced in one place, travel to the other side if the world to be processed and back again before it reaches our supermarket shelves, causing 5–6% of GGE.

Buying local produce is hugely important, so we must look at what Britain can supply us, and choose this over cheaper imported products. It is really important to look at the labels, whether this is on the packet or on the shelf for loose fruit and veg. Supermarkets are getting better at telling us the origin of individual ingredients, such as vegetables and sometimes meat and dairy, even occasionally down to the county, but as products are likely to still come from a central distribution centre, this may not be cutting down on food miles that much.

The best way is to buy meat and veg from butchers, greengrocers, or direct from the farmer in a veg or meat box. As our food becomes more processed it’s nearly impossible to know where all the ingredients have travelled from, for although the finished product might say “made in the UK”, the ingredients could be transported from anywhere in the world.

We need to all eat more seasonally and just import food we cannot grow ourselves, such as chocolate, coffee, bananas.

Processing and Packing.

This uses an incredible 8–10% of GGE, to process our food into the many, mainly plastic, packages on the shelves.

Single-use plastic is a huge and worrying worldwide pollutant, clogging rivers and seas and breaking up into micro-plastics, but never degrading fully. Plastic packaging made up 42% of all non-fibre plastic produced in 2015, and it also made up 52% of plastics thrown away.

Buying food from plastic free shops is a great choice now, and hopefully refills will make their way into the mainstream supermarkets soon but stopping all plastic packaging can have its problems. Food such as dairy, meat or fresh fruit and vegetable products do last longer which avoids food waste, but packaging could at least be more easily recyclable or compostable (source: https://www.foodpackagingforum.org/news/report-investigates-greenhouse-gas-emissions-packaging-and-food-waste).

In Somerset our packaging has one of three options after we use it: either it gets recycled, classed as non-recyclable in the general waste, or it is dropped as litter.

Some countries don’t have the same benefits of rubbish disposal that we do in the UK, and unfortunately single-use plastics frequently do not make it to a landfill or get recycled. “32% of the 78 million tons of plastic packaging produced annually worldwide is left to flow into our oceans; the equivalent of pouring one garbage truck of plastic into the ocean every minute”, (source https://www.earthday.org/fact-sheet-single-use-plastics/).

We need to really value the services we have here and educate our children about the negative impacts of plastic pollution. In Singapore, fines work well at stopping littering, and this approach could be implemented better in the UK. However, we can still act as individuals and as communities to litter pick and ensure plastic doesn’t get washed into our rivers and storm drains, eventually out to sea.

Recycling plastic has its own carbon footprint but is part of the solution. We can also look out for products to buy that reuse recycled plastic. Luckily, in Somerset our non-recyclable waste can now be burned to make electricity in Avonmouth, which is another part solution, but the best environmental choice is to reduce how much we buy in plastic packaging.

Refrigeration to sell food in supermarkets adds another 2–4% of GGE. This isn’t just from the huge freezers and (often open) refrigerators that you see in the supermarket themselves, but the refrigerated trucks that are used to transport the packaged goods.

Conclusions

It has been proved that our food is vital to saving the planet. What should we choose as concerned people?

The most important thing we can do for the health of our planet and ourselves is to improve the soil and ensure a healthy insect population, as this is the basis for all plant and animal life.

Therefore, we should only eat organic food, only eat pasture fed herbivores if we choose to eat meat at all, and give up chicken and pork unless they are raised in an agroforestry or regenerative farming system.

This can be expensive and inaccessible for many, and currently there aren’t enough suppliers to feed us all this way. Hopefully funding from governments will mean all food will be organic, arable farmers will switch to minimal till methods, industrial meat will be a thing of the past and pasture fed will become lower in price.

Before that happens, those that can afford it should try and support farmers that are braving the change, because we need to value food more as a society and pay and respect farm labourers more for the vital job they provide. For example, a local farmer who traditionally farmed arable crops for human consumption, has been forced to change to highly mechanised methods to produce animal feed, because they can’t find the workforce to handpick the crops. We need a culture that encourages young people to work on farms growing fruit and vegetables, make sure they are paid a good wage, and petition our government to support existing farmers in the switch to regenerative and organic methods by funding and incentivising them properly.

If you can’t afford organic vegetables from the supermarkets, some local veg box supplies might not have been able to afford to get official certification, but if you can trust their word by actually meeting the farmer themselves, you can buy non-certified organic fruit and veg at a lower cost.

Additionally, you would be supporting a local small farmer. You could also grow your own! Allotments were designed to provide an affordable method of growing food, and we can grow food organically and regeneratively there – this can be as little as £10 up to £50/year. We need to make sure everyone has access to land to grow food – both with more allotments and bigger back gardens.

Buying local pasture fed beef from your local butcher can be as cheap as the supermarket and eating meat less often and seeing it as a treat can make organic more affordable. When eating in restaurants and takeaways, choosing the vegan option will ensure you are avoiding industrial meat, or use guides from the Sustainable Restaurant Association.

Food should be the most important and respected aspect of our lives. It certainly is one of the most important things in terms of the environment. So, I hope we can all start to take more time to experience the joy in home cooking, experimenting with more plant based meals, using fresh, local and seasonal ingredients.

This would cut down on the waste, processing, packaging and refrigeration that our convenience food culture has resulted in and be better for our health too. It is really important we keep cooking from scratch, and teaching those who have lost the skill how to cook. Removing home economics from the curriculum in the UK was a huge error, I just hope we can get cooking back into schools as a vital skill for the next generation to learn.

In summary, we need to embrace another way: re-visiting the best of farming and home cooking from the past; but also using our new knowledge of soils and ecology to ensure that life can continue on this planet.

References and sources from a variety of media

Articles and papers:

- Land use: https://ourworldindata.org/land-use

- Pasture fed vs industrial meat: http://www.fao.org/3/ar591e/ar591e.pdf

- Regenerative Agriculture, the Solution to Climate Change: https://us11.campaign-archive.com/?u=dfce65f80d8cf5e31927ee7b4&id=63c576cc69&e=a813ebdb83&fbclid=IwAR2MfVOgdXhDqrj5KbdJjM435ItZlVu4b0XlGWRxG5SZDAlatnIQMJZlCBw

- Farming without disturbing soil could cut agriculture’s climate impact by 30% – new research: https://www.facebook.com/groups/3575792732499249/permalink/3864484883630031/

- The need for organic farming: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/jan/28/can-we-ditch-intensive-farming-and-still-feed-the-world?fbclid=IwAR0-n-pGkhfYYgCuq_7HgBEhFli6-6_S18OChGGeLPwjcxBHWB2GEX2Exsg

- Worms and other soil organisms harmed by agrochemicals: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/may/04/vital-soil-organisms-being-harmed-by-pesticides-study-shows?fbclid=IwAR3cYnL-tcjpNuLramtjCa_fHpHxEaHU0zjSZ0gSfo2WkgcEXSDvdkVtETA

- Nitrous Oxide: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-no2-idUSKBN26S35W

- The Yard Stick: https://techcrunch.com/2021/02/17/yard-stick-provides-measurement-technology-to-combat-climate-change/

- Economics of Land Degradation Initiative report (September 2015) http://www.eld-initiative.org/file admin/pdf/ELD-pm-report_05_web_300dpi.pdf

- Where to source 100% pasture fed meat: https://www.pastureforlife.org/

- Pasture fed chickens: https://www.tendrevolution.com/pages/the-pasture-raised-egg-company

- Alternative to soya feed: https://www.farminguk.com/news/uk-firm-farms-mealworms-for-sustainable-poultry-feed_58071.html

- Historically interesting: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-09/climate-change-will-reshape-earth-as-human-land-use-did

- Ancient forest gardens: https://www.shelterwoodforestfarm.com/blog/the-lost-forest-gardens-of-europe?fbclid=IwAR0aO1tCd2Q4GIaqjWEuJ7JOvERupLNj_ztDBXBZ7xKTVWop1M5lRs__-jU

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/forest-gardens-show-how-native-land-stewardship-can-outdo-nature

- Trees for the future: https://trees.org/?fbclid=IwAR3fzBpfjPGACgUJcB3vgRC7rD2xZaiPMRvehbqRI2UpAxiwE_cAvDeb3JM

- Love food hate waste: https://www.lovefoodhatewaste.com/

Short videos:

- The GHG figures from where this article is based; https://www.grain.org/e/5310

- Regenerative agriculture: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=uBngaoG_-6A&list=PLaB0XtT-WMEP-brEmhKaI8eLr_ZEeHXpE&index=1&fbclid=IwAR1SW7EeD8x2zt1L2FHMuxY_2Bre84CrhoZzjz4kVH8RGXX9kBMoFo5ebsE

- The health of the soil and hidden micronutrients- infographic: http://www.fao.org/3/BC275e/bc275e.pdf

Films:

- Kiss the ground – Netflix: https://m.youtube.com/watch?fbclid=IwAR1NluiaVEPFLFP8Q5aMVT-DMUNbe4Y4h6fDmcjH-GqCvz0X3E0Wt2QoGNU&v=3iknWWKZOUs&feature=youtu.be

- The biggest little farm: https://www.uphe.com/movies/the-biggest-little-farm

- Inhabit: http://inhabitfilm.com/?fbclid=IwAR3-95PGlJ3aBu72qVjjHKUummo7pz1dguGDVbSInU-uWdIWKHMB_77HDNY

Books:

- Wilding” – Isabella Tree, 2018

- “Meat, A Benign Extravagance” – Simon Fairlie, 2010

- “An Agricultural Testament” – Albert Howard 1940